Radical Interpassivity: Is There No Alternative?

To hell and back with the help of Fisher, Žižek, and Hall.

“This year's radical symbol or slogan will be neutralised into next year's fashion; the year after, it will be the object of a profound cultural nostalgia. Today's rebel folksinger ends up, tomorrow, on the cover of the Observer colour magazine.” - Stuart Hall, Notes on Deconstructing the Popular

“In fact, capitalist realism is very far from precluding a certain anticapitalism. After all, and as Žižek has provocatively pointed out, anti-capitalism is widely disseminated in capitalism. Time after time, the villain in Hollywood films will turn out to be the 'evil corporation'. Far from undermining capitalist realism, this gestural anti-capitalism actually reinforces it.” - Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism

Preface

Honestly, I just need to get this off my chest. If I tried to update this every time a studio churned out some new hip “subversive” slop I’d be adding prefaces until the heat death of the planet, which should be any day now. So here’s my attempt to make sense of where we are, how we got here, and what we can do, regarding the neoliberal cultural quicksand we seem to be trapped in. For this I employ the help of Mark Fisher, Stuart Hall, and my nemesis Slavoj Žižek. Enjoy, or don’t, the culture will do it for you anyway.

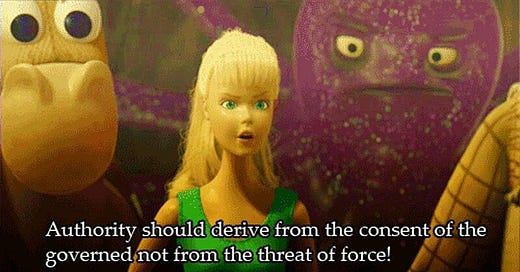

This isn’t about Barbie, but it’s not not about Barbie. I have both not seen Barbie yet nor do I care to wade into the specific discursive morass that the Barbenheimer phenomenon has spawned. This essay is, however, about what’s possible for “radical” media in our contemporary film and television production landscape. Now seemed as relevant a time as ever to update and—if you’ll believe it—shorten this into something more readable and less academic, this piece having originated in the insular bowels of The New School for Social Research. What we’re left with is something of a genealogy of today’s “popular” anti-capitalist media and an interrogation of what this politically means for us material(ist) girls in a material world.

Much has changed in the few short months since my original writing;—it ends on How to Blow Up a Pipeline, remember that?—the majority of the entertainment industry is currently on strike and an ostensibly “subversively radical” major blockbuster based on a monolithic toy “franchise” is the number one film in the world. Is this a contradiction? Does this call for a resignation to cynical nihilism in the face of corporate hegemony or does it open up spaces of hope, opportunity, and resistance? Let’s find out.

And you may ask yourself, "Well, how did I get here?"

This essay sets out not from a thesis, but a question. Is it still possible, in today’s regime of hegemonic neoliberal cultural—specifically film—production, to produce “mass” or “popular” film that has potential to actually inspire and translate to meaningful, radical, even revolutionary anti-capitalist political action? As teased in my title, this question owes a lot to Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? where he tackles a similar question but on the macro-level of neoliberal capitalism as a whole. This is essentially a variation on Fisher’s theme.

My posed question(s) is of course a virtually impossible one to prove an answer to. It is not empirically provable, very few people will light a cop car on fire and then tell a film crew “I’m doing this because of a movie that I saw.” There are of course signs and continuities that present themselves during times of political upheaval: the presence of “V” graffiti tags and Guy Fawkes masks from V For Vendetta (2005) appearing in the 2011 Occupy protests both in person and online in the form of the anti-capitalist hacker group Anonymous, the appearance of the figure of the Joker—of the Todd Phillips’ Joker (2019) variety—in 2019 protests from Lebanon to Chile to Hong Kong, and the appearance of “Handmaidens”—ala Hulu’s immensely popular The Handmaid’s Tale (2017) series based on the Margaret Atwood book of the same name—at protests usually aimed at opposing fascism or infringement upon women’s rights, especially abortion. Of course, the deployment of symbolism from popular culture does not a revolution make, nor is there any indication that this media actually inspired this political action.

The actual material, political ramifications of a film are, as mentioned, harder to pin down. However, two famous examples do stand out, one for each end of the political spectrum. I’m speaking of course about Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 Battle of Algiers—said to have inspired radical guerilla tactics in groups such as the Black Panthers and the Irish Republican Army (IRA)—and D.W. Griffith’s 1915 Birth of a Nation. It is deeply unfortunate, to say the least, that in terms of films that have inspired masses of people to political action I can think of none that achieved this on a large scale more than Birth of a Nation, which was almost single-handedly responsible for the massive resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan in the American South in the 1920’s, and famously screened at the White House by then-president Woodrow Wilson who is rumored to have described the film as “like writing history with lightning.”1 I highlight these two examples to briefly demonstrate that it at least has been possible in the past for popular or mass films to inspire radical political action.

Mise-en-scène

Suffice it to say that we are now in a much different position in almost every way than we were in 1915 or 1966. What we are dealing with today, at least in the context of the United States, is a much more homogenized film landscape with its cultural output and production largely controlled by corporate monopolies, often backed up by state funding not in the form of arts grants but in support from the US military. For example, US Air Force Major Frank Martinez recently wrote that “while the US Air Force has provided support to many Marvel films” it must “further capitalize” on a “favorable US film industry environment” by “providing direct funding, support, and experience to movies that prominently feature Air Force characters” which they claim, even more despicably, is necessary as “the service needs to increase the diversity of its recruiting” and these films provide “a far-reaching and powerful medium to show disparate parts of society the breadth of opportunities available in the Air Force.”

Of course, this is not the norm for American film production, but demonstrates the degree to which the interests of the state and capital are intertwined both with each other and as such contemporary film production. A closer look at today’s landscape paints a bleak picture. Looking at the highest 10 grossing films at the American domestic box office for 2022, all of them were based on existing intellectual property (IP) franchises, half of them were superhero movies, and they were produced and distributed by five production companies (Paramount Pictures, Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 20th Century Studios, Warner Bros., and Sony Pictures Entertainment (SPE).)

Attributing these releases to even five production companies is however misleading, as both Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures and 20th Century Studios are subsidiaries of Walt Disney Studios, which is itself under the Disney Entertainment segment of the Walt Disney Company. In fact, all these production companies make up, or are under, the “Big Five” (formerly, and tellingly, the Big Six, until 20th Century Studios was absorbed into Disney) Hollywood production studios—Universal (owned by Comcast), Paramount, Warner Bros., Disney, and Columbia (owned by Sony)—which account for an estimated 85% of all American box office revenue. If you include streaming services in this, you only add a few more corporations. Netflix remains on its own, Apple provides Apple TV, Amazon controls Prime Video (and legacy film studio MGM), and Comcast owns Peacock in addition to having a 33% stake in Hulu. The majority stakeholder in Hulu is, of course, Disney, who also runs Disney+. HBO, HBO Max, and Discovery+ are all owned by Warner Bros. Discovery, recently spun off from AT&T, and Paramount runs Paramount+. When I describe media and film production in the United States today as being in the vice grip of corporate hegemony, it is not an exaggeration.

Pure Ideology

It then follows that as corporate neoliberalism is the hegemonic order structuring American film production today that said media would have a vested interest in furthering the goals of said corporate neoliberalism, i.e., the continued expansion and accumulation of capital and profit. Here is where ideology enters the picture. Of course, ideology functions unconsciously, even the most low-budget indie film could perpetuate the dominant ideology, but corporate hegemony sure helps. Let us now turn to Slavoj Žižek for some clarification on ideology:

“The most elementary definition of ideology is probably the well-known phrase from Marx's Capital: 'sie wissen das nicht, aber sie tun es' - 'they do not know it, but they are doing it'. The very concept of ideology implies a kind of basic, constitutive naivete: the misrecognition of its own presuppositions, of its own effective conditions, a distance, a divergence between so-called social reality and our distorted representation, our false consciousness of it.”2

Following Žižek’s lead, an additional block quote from Marx himself may help us here as well:

“The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it. The ruling ideas are nothing more than the ideal expression of the dominant material relationships, the dominant material relationships grasped as ideas.”3

To translate this to our context, cultural ideological production under capitalism is almost inherently imbued with the aforementioned dominant ideology—which we’ll soon see Žižek posit as commodity fetishism—as it’s a product of this ideology, which serves to recreate and reinforce itself regardless of, or in some instances in spite of, the commodity’s content. Understanding ideology’s role in film production then begs my original question, can we get outside of it? Or if not, can we work against it? Can we use the master's tools to dismantle the master’s house? And if not, can we produce films against this hegemony that stand any realistic chance of reaching a mass audience, thus becoming mass or “popular” culture, and inspiring action?

Žižek, Hall, and Fisher all rightly point to the fact that representation of the radical in film and media does not necessarily equate to material actualization of these politics. For Hall, it’s a kind of begrudging given that “this year's radical symbol or slogan will be neutralised into next year's fashion” and he insists on the historic specificity, constant change, and potential re-articulation of virtually all culture. For him this opens up just as many possibilities as it forecloses, what matters is not “the intrinsic or historically fixed objects of culture” but “the state of play in cultural relations”, or “to put it bluntly and in an oversimplified form - what counts is the class struggle in and over culture.”4 While Fisher, and to a (much) lesser extent Žižek, also desire to point to a way out of this trap, they go a step further in the identification of the problem. It is not only that capitalist culture will consume, co-opt, and sell back to us our own forms of protest and resistance, but that in doing so it satiates the masses desire for this political action, acting not as “neutralized” but neutralizing.

Here Žižek deploys Robert Pfaller’s term which makes up the other half of my title, interpassivity. Žižek describes interpassivity against interactivity, a situation in which we think we’re in control but are in fact ceding control, a situation in which “the object itself takes from me, deprives me of, my own passive reaction of satisfaction (or mourning or laughter), so that it is the object itself which 'enjoys the show' instead of me, relieving me of the superego duty to enjoy myself.” Žižek uses examples of Western leftist intellectuals thinking—thus “making”—themselves “revolutionaries” by “admiring Cuba” or “'democratic socialists'” by “endorsing the myth of Yugoslav 'self-management' Socialism as 'something special', a genuine democratic breakthrough.” He continues that “in all these cases, they have continued to lead their undisturbed upper-middle-class academic existence, while doing their progressive duty through the Other.” He clarifies however that it’s not that the audience, the subject, is deprived of their enjoyment, if this was the case these movies would not have the mass appeal they do. He posits that this odd phenomena is possible due to a paradox of the superego, that:

“the only way really to account for the satisfaction and liberating potential of being able to enjoy through the Other - of being relieved of one's enjoyment and displacing it on to the Other - is to accept that enjoyment itself is not an immediate spontaneous state, but is sustained by a superego imperative: as Lacan emphasized again and again, the ultimate content of the superego injunction is 'Enjoy!'.”

What Žižek means here is that the superego produces an imperative to enjoy which results in a paradox, after all can one be forced to enjoy something? Or as he puts it: “perhaps the briefest way to render the superego paradox is the injunction 'Like it or not, enjoy yourself!’” Without getting too into the psychoanalytic weeds let’s look at two further clarifications from Žižek, who concludes that “against this background, it is easy to discern the liberating potential of being relieved of enjoyment: in this way, one is relieved of the monstrous duty to enjoy.” He then distinguishes between two different forms of interpassivity, the first of which relates to commodity fetishism and is the one useful for our purposes:

“In the case of commodity fetishism, our belief is laid upon the Other: I think I do not believe, but I believe through the Other. The gesture of criticism here consists in the assertion of identity: no, it is you who believe through the Other (in the theological whimsies of commodities, in Santa Claus...).”5

What does this mean for our central question? Essentially that through the representation in the cultural commodity (the film), which in its existence reproduces commodity fetishism, the subject (audience) is relieved of their anxiety about not doing something via the Other doing it, or enjoying it, for them. This I believe is the crux, or the trap, of interpassivity in relation to film under capitalist cultural production hegemony. Let’s now return to more stable, and decidedly less psychoanalytic, ground with Fisher and see what he has to say on this matter.

Fisher provides a perspective that seems to live somewhere between Hall and Žižek, with a dash of Deleuze added for good measure. In following Deleuze, albeit in a decidedly more materialist tract, he highlights capitalism’s devouring nature which seems to also be its ability to adapt, change shape, be plastic, writing:

“When it actually arrives, capitalism brings with it a massive desacralization of culture. It is a system which is no longer governed by any transcendent Law; on the contrary, it dismantles all such codes, only to re-install them on an ad hoc basis. The limits of capitalism are not fixed by fiat, but defined (and redefined) pragmatically and improvisationally. This makes capitalism very much like the Thing in John Carpenter's film of the same name: a monstrous, infinitely plastic entity, capable of metabolizing and absorbing anything with which it comes into Contact.”

This both rings true in terms of capitalism’s material reality, its ability to adapt, seize upon, and benefit from crises, and echoes Hall’s earlier assertion that capitalism’s devouring drive should be taken as an assumed given, a fact. It’s not a matter of if capitalism will co-opt your radical movement and sell it back to you, but when.

He edges away from Hall and closer to Žižek in further insisting that once capitalism has recognized acceptable forms to devour it goes from taking a reactive, passive role, to an active one, taking over the shaping of your desire for you without—as again is the nature of ideology—you realizing it. He writes that what we are dealing with now is “not the incorporation of materials that previously seemed to possess subversive potentials, but instead, their precorporation: the pre-emptive formatting and shaping of desires, aspirations and hopes by capitalist culture.” While I don’t believe that Fisher is a cynic, he does take a more negative view of the reappearance of cultural forms than Hall, especially within the context of late capitalism. He employs the example of “countercultures” that “endlessly repeat older gestures of rebellion and contestation as if for the first time which in his view “don't designate something outside mainstream culture” but rather “they are styles, in fact the dominant styles, within the mainstream.”

Fisher then leans even more heavily into Žižek and again insists on a focus on interpassivity. Here he uses the example of the film Wall-E:

“A film like Wall-E exemplifies what Robert Pfaller has called 'interpassivity': the film performs our anti-capitalism for us, allowing us to continue to consume with impunity. The role of capitalist ideology is not to make an explicit case for something in the way that propaganda does, but to conceal the fact that the operations of capital do not depend on any sort of subjectively assumed belief. It is impossible to conceive of fascism or Stalinism without propaganda - but capitalism can proceed perfectly well, in some ways better, without anyone making a case for it.”

I think Wall-E is a particularly good example here. It’s not so much a film that has imbibed anti-capitalist messages and sold them back to us with honest “intent” (examples of which we’ll soon see) but was constructed and produced in its very origin to serve the ideological function of commodity fetishism reification via the now-hip style of anti-capitalist critique. Put more bluntly, Wall-E was a Pixar film, a Disney film, and thus a commodity sold to us under the guise of “popular” anti-capitalism whose very purpose was to reinforce commodity fetishism in the service of one of the largest media monopolies on earth. This can also be said of a film like Barbie. While this ends up being the actual result of most films, no matter how vehemently anti-capitalist, within this mode of film production, there is a marked difference in being produced in the “belly of the beast” as it were. Relatedly, I’m very grateful for both of our sake that Fisher understands, and can thus clarify, Žižek better than myself. This is evident in a brief but revealing passage where I think Fisher sums up in a few lines what Žižek spent dozens of pages on:

“Capitalist ideology in general, Žižek maintains, consists precisely in the overvaluing of belief - in the sense of inner subjective attitude - at the expense of the beliefs we exhibit and externalize in our behavior. So long as we believe (in our hearts) that capitalism is bad, we are free to continue to participate in capitalist exchange.”6

When put this way it seems almost confoundingly obvious. Of course capitalist ideology overvalues self-belief, the individual inner attitude, both because of its incessant drive to individualism (the most malleable subject unit) and to obscure, via commodity fetishism, the structural nature of the illusion and one's place in it.

The Revolution Will Be Television

Following from Wall-E, I’d like to identify a category of films that I find more “cynical” in their performance of “anti-capitalism for us,” namely those that are produced from their very beginnings within the bowels of the capitalist strongholds themselves. I’d like to call this category Capitalist Anti-Capitalism. Included in this would fall films that take on a latently or explicitly radical veneer to the ends of reifying commodity fetishism and making some multinational media conglomerate hundreds of millions of dollars. (Again, this seems to be firmly where Barbie falls.) The most egregious example of these types of films, if you’ll allow me a brief trip to 2018, is Ryan Coogler’s box office giant Black Panther.

Black Panther has it all: The “bad guy” (Michael B. Jordan’s Killmonger) calling for the arming of the international Black proletariat against the exploitative forces of settler colonialism, only to inexplicably become a “terrorist” in third act where the “villain” has to call for some absurd violence to make clear to the audience that they’re actually the “bad guy” despite correctly identifying many of society’s problems, a trope that goes repeated in virtually every superhero film these days. It has the co-option of the name of one of the most famous American communist organizations of all time in the service of a “superhero” who works with a literal CIA agent (Martin Freeman, portrayed as a “good guy”) to crush the aforementioned “bad guy” and go about things the “correct way” by joining the UN and establishing an NGO in Oakland (the original home of the Black Panther Party.)

The message of the film is an unequivocal, full-throated endorsement of liberal capitalism and its status quo system of nation-states. It is saying to the audience “sure, it might be cathartic to steal back African artifacts from the British Museum or arm the Black proletariat against their oppressors, but violence is never the answer, just fall in line and be nice to the people in the suits and if you’re lucky you might get a seat at our table.”

Furthermore, Black Panther echoes the earlier article by the Air Force Major calling for greater military engagement in the production and funding of Marvel films to the ends of “increasing diversity,” a logic which Black Panther deploys with masterful cynicism. Wrapped in the guise of a Black empowerment film it takes pains again and again to show Killmonger as the “bad guy,” the CIA as the “good guy,” and demonstrates an insultingly ahistorical view of US international relations with Africa in being painted as a sort of benevolent ally who, when push comes to shove, is just here to help. Suffice it to say, Black Panther was the second highest grossing film of 2018 worldwide raking in over $1.3 billion, second only to Avengers: Infinity War.

Black Panther is of course only one instance in this (now) long, wretched tradition. Others include Wall-E, The Lego Movie, Black Panther 2: Wakanda Forever, Star Wars Episode VIII: The Last Jedi, Joker, Disney’s Star Wars series Andor, and now Barbie.

The Revolution Will Be Televised

I find the flipside of this coin much more interesting and less insidious, and as such, harder to parse through. I’ll call this category Anti-Capitalist Capitalism, the capitalism here being not always intentional yet in one way or another these films end up generally used to further capitalist ends, at least financially. This is not to say of course that any film that makes money can’t be meaningfully anti-capitalist, just that often the critique in the film gets lost in the spectacle and associations of its production and distribution. Or at the very least, that in reaching a certain critical “mass” the film actually loses its radical potential by nature of becoming deferred passive consumption, thus again perpetuating interpassivity. This presents a very thorny challenge to radical filmmakers that I’d like to think through here.

I’ll start off, I think quite charitably, with the work of South Korean filmmaker Bong Joon-ho. Many of his films contain a strong critique of capitalism, a critical project he was undertaking long before his rise to prominence eventually culminating in the excellent, albeit implicated, Parasite (2019). His 2013 Snowpiercer and 2017 Okja, the latter being produced and distributed by Netflix, were both explicitly anti-capitalist films focusing on issues such as ecology, food production, and social stratification. Interestingly, this more explicit anti-capitalism also marked his turn to directing English-language films, with Snowpiercer being his first.

The case of Okja is a notable one as it also marked, in my understanding, the turn of massive studios/corporations such as Netflix toward seeking out explicitly anti-capitalist content. Due to being produced by Netflix, Okja was actually ill-received at more prestigious film festivals seen to be bastions of taste, culture, and even potentially counterculture, free from the schlock of the American media giants. When it premiered at the Cannes Film Festival it was met with mixed boos and scattered applause for this reason. His next film, Parasite, returned to the Korean language and a non-corporate Korean production company. Arguably his most explicitly anti-capitalist, Parasite went on to win enormous acclaim and international box office success. It won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, the festival he’d previously received boos at, and later won four Academy Awards at the Oscars including Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, Best International Feature Film, and the most coveted prize in filmmaking, Best Picture.

Now, anti-capitalist films have been awarded Oscars before. A film winning an Oscar does not immediately translate it into “mass” culture. When I was growing up in the 90’s and early 2000’s the Oscars had an almost pretentious reputation, there was a pernicious idea that Oscars only went to “art films” (which is wildly untrue.) In the intervening few decades the spectacle of Oscars promotional “For Your Consideration” campaigns have become pervasive, akin almost to political campaigns, where studios shell out millions of dollars in gifts, events, advertising, and press circuits to try and garner their film a coveted Academy Award. While the Oscar winners are still technically decided by the 10,000+ voting members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, like all things Hollywood, they are not outside of, or immune to, the tendrils of capitalism. As such, I remember being absolutely floored that Parasite won any awards at all, especially Best Picture. It was an outlier, a bit of a dark horse, an international production by a director still relatively unknown to American audiences despite the success of Okja, and worst of all for American audiences, they had to read subtitles.

Parasite is an excellent film and its Oscars were much deserved. Nothing about the production of the film indicated that it would go on to enjoy the success that it did, and it was not subject to any of the pressures from the Hollywood film studio ideological apparatus. However, I include it here both in the way that it was cheered on to an almost uncomfortable degree, as if to say “we get it guys! We’re hip! We hate capitalism too!” and for the era that it ushered in, which we will now turn to.

If Parasite was a bug then the following glut of anti-capitalist cinema has been a feature. The most obvious, immediate offspring of the Parasite phenomena was Netflix’s 2021 South Korean dystopian series Squid Game, the production of which was announced by Netflix in September 2019, actually before Parasite won its Oscars but at the height of its pre-Oscar buzz. Squid Game is a “survival drama” in which poor people are essentially forced to fight each other to death in increasingly complex “games” where the winner gets an enormous cash prize. Think class-warfare Battle Royale. Squid Game was released in September 2021 to massive success, yet similarly to Okja it garnered some side-eyed criticism for this supposed masterstroke of anti-capitalist criticism being produced and distributed by a corporation worth $147 billion (as of this writing.) Almost as if to prove the critics points, Netflix then announced that they’re developing an actual reality television program based on Squid Game, to be filmed in the UK, in which people compete for a cash prize of £4.56 million. Satire is dead, long live satire.

Another legacy of Parasite’s Oscars success appeared at the 2021 Oscars in the unlikely form of the ghost of Fred Hampton. I’m of course referring to Shaka King’s 2021 pseudo-biopic Judas and the Black Messiah, which roughly follows the story of the Chicago Black Panther Party (BPP) leader Fred Hampton who was assassinated in 1969 at age 21 by officers from the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office, with assistance from the Chicago Police Department, and in coordination with the FBI. The film starred Daniel Kaluuya and LaKeith Stanfield as Fred Hampton and the BPP FBI informant William O’Neal, respectively. Much like Parasite, Judas and the Black Messiah did quite well at the Oscars with both Kaluuya and Stanfield being nominated for Best Supporting Actor,7 wherein Kaluuya won for his portrayal of Fred Hampton. There’s obviously a level of cognitive dissonance in an actor winning an Oscar for portraying someone who so radically stood against everything that a bourgeois spectacle like the Oscars exemplifies, which I’ll elaborate on in a moment, but this did not stop Kaluuya from speaking to the debt owed to Hampton—while also simultaneously avoiding any mention of his radical politics instead framing it as Hampton and other BPP leaders “showing me how to love myself.” as we see in this excerpt from his acceptance speech:

“And to Chairman Fred Hampton. Bro, man. Man, what a man. What a man. How blessed we are that we lived in a lifetime where he existed, do you understand? You know what I mean? Like, thank you for your light. He was on this earth for 21 years, 21 years, and he found a way to feed kids breakfast, educate kids, give free medical care, against all the odds. He showed, he showed me, he taught me – him, Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale, the Black Panther Party – they showed me how to love myself. And with that love they overflowed it to the Black community and to other communities. And they showed us that the power of union, the power of unity, that when they play divide and conquer, we say unite and ascend. Thank you so much for showing me myself. And yeah, man, there's so much work to do, guys. And that's on everyone in this room. This ain't no single-man job. That's some [unintelligible]. And I look to everyone, every single one of you. You've got work to do, do you understand?”

Yet another virulent symptom of the Parasite effect—and general rise in popular anti-capitalist sentiment since 2016—is the Adam McKay Industrial Complex. McKay is an admittedly insufferable filmmaker who got his start making sophomoric Will Ferrell comedies such as Anchorman, Talladega Nights, and Step Brothers. In the last few years he’s pivoted to being something of a self-styled socialist, directing The Big Short,—a satire/drama following the 2008 financial crisis—Vice, a flat, ineffective critique of Dick Cheney and the Bush years, and the stunningly cynical Don’t Look Up. On the producing side of things, he produced 2022’s very tiring The Menu, and along with Will Ferrell also produces the enormously successful HBO show Succession. All five of his newer projects share the same theme: “rich people bad, aren’t we so clever for knowing this?” which is about where it all starts and ends. Of course, McKay is also apparently producing an HBO limited series based on Parasite, with Joon-ho also serving as executive producer.

McKay is not alone in capitalizing on the newfound popularity of anti-capitalist media to produce shallow, toothless “critique.” Rian Johnson, director of the aforementioned Star Wars VIII: The Last Jedi, directed 2019’s star-studded murder mystery Knives Out—more anti-Trump than anti-capitalist—and it’s abysmal 2022 sequel Glass Onion, avowedly anti-capitalist in everything but form and content. Not to be left out, Mike White wrote and directed HBO’s class-critique-by-way-of-miserable-rich-people-on-vacation hit series White Lotus, which swiftly ushered in contemporaries in the same genre, namely 2022’s Triangle of Sadness (which garnered Oscar nominations) and 2023’s Infinity Pool. To be fair, these latter two films are better than anything Johnson and McKay have ever touched, with Infinity Pool remaining such a cut above the rest of these that I feel bad even mentioning it.

This onslaught of popular anti-capitalist film and television being produced by larger and larger studios, with shallower and shallower critique, is what led me to ask my original question about the possibility of revolutionary potential in this media today. While I think there is a world of difference between Shaka King’s somewhat misguided attempt at bringing Fred Hampton to a massive audience, and McKay and Johnson’s smarmy, self-satisfactory liberal wish-fulfillment fantasies, I think both end up unfortunately reduced to producing interpassivity. Although of course Judas and the Black Messiah does contain more latent radical potential—in the sense that it could actually turn people on to the intensely radical work and legacy of Fred Hampton, the role of state forces, the FBI, and COINTELPRO in his murder, or even lead them to watching the excellent 1971 documentary The Murder of Fred Hampton—this potential still remains secondary to the actual form, content, and impact of the film.

I am of course not the first to notice this, and within the last year or so it seems that people have reached a point of weak-anti-capitalist-critique fatigue. In late 2022 and early 2023 this malaise started to make itself visible in the headlines of various media outlets: “Why all “Eat the Rich” Satire Looks the Same Now” in December 2022, with “Sorry Hollywood, I’ve lost my appetite for Eat the Rich Movies” and “The Movie Industry’s Confused Eat the Rich Fantasy” shortly following in February 2023. The timing of all of these coincided with yet another year of anti-capitalist films being up for many Oscars, 2022’s contender being Triangle of Sadness.

Perhaps indicative of this fatigue, Triangle of Sadness took home zero of the three awards it was nominated for. It would be remiss of me to not highlight that all three of these article titles reference the phrase “Eat the Rich”, a variation of which—"Tax the Rich”—New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) controversially emblazoned on her gown at the 2021 Met Gala, upsetting people on virtually every end of the political spectrum and I think marking the increase in popular sentiment of people noticing the gulf between radical messages, discourse and meaningful action. Patrick Sproull highlights this very phenomenon in his critique, writing “even the phrase “eat the rich” feels trite. It neatly sums up a tote bag slogan era of anti-capitalism in culture, cutesy shorthand that’s now entirely representative of a watered down, inoffensive type of politics.”

All three of these articles point heavily to Triangle of Sadness, The Menu, and Glass Onion as the focus of their critique, highlighting how this “critique” loses its edge both in the liberal, petit bourgeois sensibilities of these films and in the popularizing of such an easily digestible critique, allowing the audience to pat themselves on the back for a job well done at the cinema. Again, “so long as we believe (in our hearts) that capitalism is bad, we are free to continue to participate in capitalist exchange.” This theme pointed out in the early 2000’s by Žižek and Fisher makes its way into all these critiques of the now thoroughly sanitized anti-capitalist-critique film.

For Vulture, Sam Adler-Bell writes that “there is an element of feeble wish fulfillment in these works, an unctuous eagerness to flatter the audience’s moral sensibilities while satiating a furtive lust for class warfare” that has now become so popular and prevalent that “somehow, hostility to the ultrarich has become a marker of modish cultural literacy.” Adler-Bell accurately identifies one core issue with the critique in these films as well, namely that “they are not concerned primarily with the old Marxist conflict between owning and working classes.” This is of course not to say that if everyone and everything were Marxists the revolution would happen tomorrow, but again it would sure help. Adler-Bell, similarly to myself, also situates Parasite as both the almost-accidental beginning of this current cultural shift and as a critique that actually understood its focus of critique, generating only pale imitations in its wake. He writes, specifically (and rightly) critiquing the aforementioned films muddled understanding of the service economy, that:

“Parasite’s insight is an inversion of that which animates its successors: If The Menu and Triangle of Sadness clumsily conjure the service workplace as a theater for retributive violence, Parasite demonstrates that even an idealized vision of class compromise in the care economy — a family of takers embedded completely into a family of havers, in which intra-familial desire and inter-familial exchange are mingled harmoniously — ultimately invites its own eruption of barbarity.”

These limp critiques are however not the only films on trial here, and Judas and the Black Messiah does not simply get a pass for portraying Chairman Fred. One major omen that the film would not live up to its protagonists legacy was the inclusion of Ryan Coogler, director of Black Panther, as producer. I have spilled enough ink on Black Panther in this essay to make clear why this poses problems. Don’t just take my word for it though, take the word of former Baltimore Black Panther Party leader, and political prisoner of 44 years, Eddie Conway: “I know it [Judas and the Black Messiah] did a fairly broad, kind of surface presentation of Chicago and Fred Hampton and so on.” For Conway, most of the problem of the film came in what was left out, including the mischaracterization of Hampton stealing ice cream and getting sent to jail for it, where in reality he did steal ice cream but to the ends of redistributing it to a starving community:

“It’s stuff like that that’s left out that gives you the impression, well shit, he stole ice cream, he was a criminal, he was supposed to be on his way back to jail, when in reality that was all part of his struggle.”

Another issue that Conway took, along with many others, was the portrayal of Hampton and O’Neal by actors in their early 30’s and late 20’s, respectively, when in reality Fred Hampton was 21 when he was murdered, and O’Neal was 20:

“They were all young. But they looked like they were depicted as if they were hard, seasoned, and cold adults, and I think probably part of that is that it didn’t give a sense to how young the Black Panther Party’s membership was. It was mainly young people, and it was mainly women on top of that. There were professional people, but there were young people from high school, young people just starting college, young people from the neighborhood itself. I don’t think you got that. The youth was there.”

This popularization of soft, palatable anti-capitalist critique provides an interesting conundrum for left radicals today. On the one hand, surely it must be a good thing that radical, anti-capitalist critique has become so immensely popular and mainstream, that it’s viewed as a mark of hip cosmopolitanism to self-identify as some kind of socialist. I can only imagine that the socialists, communists and left radicals of pre-2008 America would scarcely have believed you if you told them that by 2021 it would be not only culturally acceptable, but fashionable, to award an Oscar for a portrayal of Fred Hampton. On the other hand, Adler-Bell and others are right to point to the fact that this waters down radical critiques and dilutes their potency if they don’t translate to meaningful political action.

By any measure consciousness has obviously been raised: we’ve seen this in everything from socialists being elected to local and national office again, to the largest protests in US history taking the form the 2020 radical George Floyd uprisings. Of course, it’s hard to see the positive out of any of this when we are still both firmly in the reactionary backlash of said protests and living under an increasingly repressive ultra-capitalist state that shows no signs of letting up, but we push on.

How to Blow Up a Discourse

Having firmly cemented both the categories of Capitalist Anti-Capitalism and Anti-Capitalist Capitalism let’s move to a category of contemporary films that don’t fall into either category. These are films produced with specifically very left-radical intent—often by self-identified communists, anarchists, etc.,—although end up in one way or another being imbricated within the productive machine of popular culture which can have varying effects on the power of their critique, and thus their potential to inspire radical action. This imbrication generally takes place via the distribution of the film, where if the filmmakers want it to make any money or be seen by a wide audience the rights must be acquired by a usually large distribution company.

One prime example of this type of film is the previously mentioned Sorry to Bother You, written and directed by avowed communist Boots Riley (of the radical hip hop group The Coup, famous for their song The Guillotine) wherein an Amazon-like company is shown to be perpetuating all kinds of social evils which can only be addressed through a radical, collective workers uprising. Films like Sorry to Bother You that fall into this murky third category, which I don’t have a name for, are the trickiest to figure out for the left regarding the films—and our—relationship to the current dominant mode of cultural production.

I.e., you can make the most radical, agitational, independently funded propaganda film you want, but if no one sees it, is it effective propaganda? But if you get picked up for distribution by a company who will inevitably be, in one way or another, beholden to the worst aspects of capitalist cultural production, have you sold out or betrayed your leftist values? This is a paradox that the left is currently grappling with which arose recently in the example of 2023’s How to Blow Up a Pipeline, based, astonishingly, on Andreas Malm’s Verso book of the same name.

How to Blow Up a Pipeline is an interesting case in that, as evidenced by its title, is an explicit call to action to destroy the capitalist fossil fuel infrastructure that is swiftly rendering much of our planet uninhabitable. There is an open understanding that this is essentially advocating for what the powers-that-be can, and often do, understand as terrorism, which is explicitly addressed in the film. To quote from the New York Times review of the film, aptly titled “Will We Call Them Terrorists?”:

“People are drinking from red Solo cups. Someone has a flask. A joint is circulating. There’s laughter and passionate debate and easy alternation between the two. With the sound turned off, the scene would be so familiar — just young adults, relaxing — that you would never guess the question they’re working through together: Are we terrorists? Do we feel like terrorists? “Of course I feel like a [expletive] terrorist!” one young man says, laughing. “We’re blowing up a goddamn pipeline!” … “They’re going to call us revolutionaries,” one young woman suggests, waving the joint for effect. “Game changers.” Not so, another counters. “They’re going to call us terrorists. Because we’re doing terrorism.””

This is clearly no Glass Onion or The Menu. However, despite the films very explicit call for direct action and vocal critique of capitalist society, How to Blow Up a Pipeline has faced criticism from various segments from the left—and obviously the right—which range from the film not being radical enough to the film being morally and ethically “compromised” due to such tenuous links as screening at film festivals that take sponsorship from oil companies, or one of the producers being linked to the obnoxious-yet-benign New York downtown scene known as “Dimes Square.”

Radical New York based cinema group Cinemovil published an essay on Medium entitled “The Bomb Hardly (Agit) Pops” in which these “critiques” are articulated, which for me both ring hollow and raise questions about ideological and moral purity on the left; (again) its relationship to cultural production, and what is even possible today. For example, Cinemovil indicts the fact that the film crew had a federal authority on set overseeing the scenes involving the construction of bombs both to ensure accuracy and to ensure that enough steps were left out of the process that one couldn’t watch the film and learn how to actually build a bomb:

“In the Q&A, [the director] Goldhaber made clear that the film’s technical advisor, an anonymous “higher-up” at the US Bureau of Counterterrorism, helped them expurgate the bombing procedural “to make sure,” as Goldhaber put it, “that we weren’t doing anything dangerous by putting anything into the movie… We didn’t want to do something bad by making the film.” Like influencing audiences to destroy property to affect change? For sabotage to sustain and elude authorities, it must produce copycats.”

This critique neglects to mention the fact that had this person not been on set, or had the film explicitly shown every step of how to build a bomb along with a call to use it against corporate and state infrastructure, the film would not have been allowed to be released. As noted in the Washington Post article “What’s Stopping ‘How to Blow Up a Pipeline’ from telling you how?” the First Amendment “broadly protects speech, even speech that could or does lead to a crime, with a few carveouts.” Author of the piece Sophia Nguyen points out that one of those “carveouts” is “incitement,” wherein the Supreme Court said in 1996 that “there’s a difference between lawful persuasion (which is protected) and speech “intentionally directed to producing an act of imminent unlawful violence” (which isn’t).” Furthermore, she notes that there’s a federal statute that specifically makes it a crime to “to teach or demonstrate the making or use of an explosive with the intent that the information be used ‘for an activity that constitutes a federal crime of violence.’” In short, had How to Blow Up a Pipeline been explicit enough in its bomb making instructions to “sustain and elude authorities” and “produce copycats” it would have been relegated to the dusty shelves of banned cinema, potentially only viewed at Anarchist house-screenings or other small, underground venues.

This is only one example of my issue with Cinemovil’s critique, but it in my view indicates the nature of the argument as essentially bad-faith holier-than-thou political moralizing. As the left goes, there will always be elements of this. It is of course good to have people pushing against things as “not radical enough” to maintain a sharp critique and avoid getting complacent—as we’ve seen in our previously mentioned films—in addition to constantly pushing the boundaries of what’s possible, shifting the “Overton window” as it were. Yet doing so to the point of an unrealistic ideological purity—as Fisher, Zizek, and Hall would agree—only ensures the contemporary left’s continued weakness.

How to Blow Up a Pipeline was only released widely at the end of April 2023, playing in 530 theaters. It’s been met with generally positive reviews, and while the budget of the film is unavailable online it does not look as if it’s made back its budget in box office revenue. Outside of some Fox News fear mongering and the “Kansas City Regional Fusion Center”—a “fusion center” being a conglomeration of local, state, and sometimes federal intelligence agencies—issuing a “Situational Awareness Bulletin” three days before the release of the film stressing agencies to be on alert “concerning a developing threat targeting Critical Infrastructure and Key Resources (CIKR), especially oil and natural gas pipelines,” How to Blow Up a Pipeline has come and gone with a whimper, not a bang. This can be read in either direction: one could argue that as the film wasn’t radical enough it’s just been made into a passively consumable piece of media that didn’t make a dent on public consciousness, or alternatively that because it’s too radical coverage of it has been suppressed as to ensure it doesn’t gain traction in the popular imagination. From where we stand today, it doesn’t seem to have made enough of an impact to merit any conclusion at all.

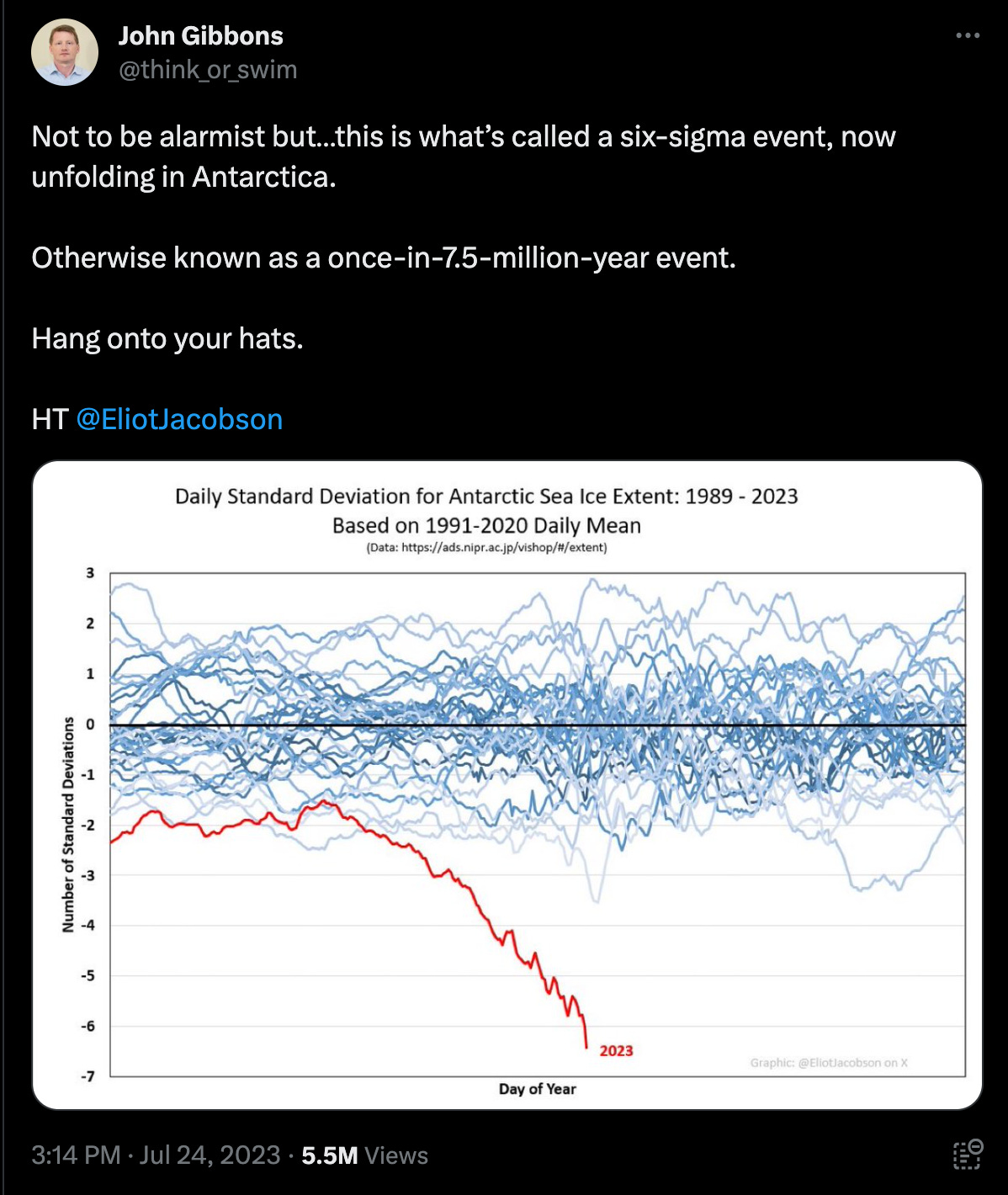

However, in the time since HTBUAP’s release the world has experienced the hottest week in history, Antarctica’s sea-ice coastlines have essentially started disappearing for the first time, and record breaking heat waves that would have been “virtually impossible” without human-drive climate change are devastating the American southwest, large swaths of Europe, and China. History will undoubtedly vindicate HTBUAP, but it remains to be seen whether anyone will be left to care.

Meanwhile, as if to say “fuck you” to me specifically, over the course of re-writing this Mattel has announced—following the success of Barbie—fourteen new property films in development including: Polly Pocket, Hot Wheels, Barney, Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Robots, American Girl, Magic 8 Ball (??), and fucking Uno. Our very own Fred Hampton, Daniel Kaluuya, will be producing Barney. Maybe we should be asking how to blow up a media conglomerate.

And you may ask yourself, “How do I work this?”

So where does this leave us regarding the radical potential of film today in its ability to inspire potentially revolutionary or radically anti-capitalist action? I think, following Stuart Hall, that it’s historically contingent, and in our contemporary era thus remains to be seen. Our theorists come down on various points regarding moving forward. In ending his essay, Hall again points to this historical contingency as a potential rupture that allows for a terrain of struggle, which he insists must be contested. If you’ll forgive another block quote, he writes:

“Sometimes we can be constituted as a force against the power bloc: that is the historical opening in which it is possible to construct a culture which is genuinely popular. But, in our society, if we are not constituted like that, we will be constituted into its opposite: an effective populist force, saying 'Yes' to power. Popular culture is one of the sites where this struggle for and against a culture of the powerful is engaged: it is also the stake to be won or lost in that struggle. It is the arena of consent and resistance. It is partly where hegemony arises, and where it is secured. It is not a sphere where socialism, a socialist culture - already fully formed - might be simply 'expressed'. But it is one of the places where socialism might be constituted. That is why 'popular culture' matters. Otherwise, to tell you the truth, I don't give a damn about it.”

Hall has less to say on the “how” regarding accomplishing this in such a heavily corporate hegemonic landscape such as ours today, however this is forgivable given the 1981 context in which he was writing. I nonetheless agree with him that we cannot simply cede this ground as overdetermined to failure or impossibility. While we may not be able to dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools, it does not mean we should leave the master's house intact.

For Fisher, contrary to his reputation as a cynic, he points to several potential ways forward imbued with his quite specific form of left-politics. In implicit agreement with Hall, he insists that the “long, dark night of the end of history has to be grasped as an enormous opportunity” wherein the “very oppressive pervasiveness of capitalist realism means that even glimmers of alternative political and economic possibilities can have a disproportionately great effect.” If anything, this view begets an optimism that we’ve seen more and more of the deeper that we get into our contemporary compounding crises, that while crisis can spell disaster so too can it spell potential salvation. However, Fisher does have a completely understandable pessimistic view of the (then) contemporary left and puts forward a few theses on what he sees as necessary for us to meaningfully confront capitalist realism today. This is not so much a program as a series of suggestions, including:

“The left should argue that it can deliver what neoliberalism signally failed to do: a massive reduction of bureaucracy.”

“What is needed is a new struggle over work and who controls it; an assertion of worker autonomy (as opposed to control by management) together with a rejection of certain kinds of labor (such as the excessive auditing which has become so central a feature of work in post-Fordism).”

“What is needed is the strategic withdrawal of forms of labor which will only be noticed by management: all of the machineries of self surveillance that have no effect whatsoever on the delivery of education, but which managerialism could not exist without.”

These are undoubtedly interesting proposals that aim at destroying a lot of what exemplifies contemporary neoliberalism, working at the lynchpin of its failed promises and delivering on them in a socialist register. He however also critiques strikes as a tactic, which I disagree with, but I take his point in regards to targeting the very forms of labor themselves and attacking or reshaping them at the structural point of production. In the context of film this points to something important, namely the extremely rigid, hierarchical structure of contemporary film production. I think that if we want to make movies against capitalism, we should seek to make them against capitalism. Not only in form or content, but in the production itself, obviously within the bounds of still-necessary elements like funding. This is a bit of a pet insistence of mine as I worked in the film industry for five years, but that’s a diatribe for another essay.

Žižek does not have much to say in the way of “ways out” of this crisis of capitalist cultural production, in my view—and true to his nature—he’s most useful as an analyst, with his political conclusions always leaving a bit to be desired. Instead, I will end by returning to someone intimately familiar with the political struggle against capitalist hegemony, Eddie Conway. While Conway has his critiques of Judas and the Black Messiah, he does not take a defeatist or pessimistic approach that it’s just Hollywood gobbling up radical symbols and selling them back to us. He has no illusions about this of course, stating that “Hollywood did what it did, and it’s always gonna do what it do” but in the next breath continues “however we can take that product, and use that product, and we use it for education.” He sees hope and potential in using even flawed media to reveal the truth behind the fiction and educate those on these legacies against its sanitized portrayal, insisting that “the things that were left out were the things that we, as activists, as organizers, need to critique.” Not to be misinterpreted, he makes his point explicitly clear:

“We’re not talking Bernie Sanders’ kind of socialism, that’s not what Fred was saying. We’re not talking Jesse Jackson’s kind of rainbow coalition, that’s not what Fred was doing. We need to convey that, communicate that, critique it, and use it. Use it as a product to communicate and educate.”

Personally, I come down with a kind of “all of the above” approach. We need critique of existing lukewarm anti-capitalist media that just serves to reify commodity fetishism, but not abandon the terrain of struggle as a foregone conclusion despite this tendency. Hegemony is not permanent or unchallengeable and in fact can necessitate a counter-hegemony. I agree with Conway that we can also use this existing media to produce not only better immanent critique, but hopefully through that critique better media itself.

It is, for me, a good thing that How to Blow Up a Pipeline exists, as every step in this direction opens up different avenues of possibilities and potentially points to the cracks in hegemony and potential for rupture that Hall and Fisher point towards. We need to be smart, critical, intentional, and un-precious about ideological or, dare I say, even financial purity.

The crisis necessitates trying anything and everything, really. While I think we face an uphill battle, anti-capitalist politics has made its way today into “popular” culture for better or for worse, with an unfortunately smirking liberal bourgeois sensibility. It’s up to us to wipe that smirk off its face. Reject interpassivity, embrace the struggle.

It’s still debated whether Wilson ever actually said this direct quote, although historian Mark E. Benbow, in searching for the origin of the quote, concluded that “More important than whatever was said or not said, Wilson gave the filmmakers all the endorsement they needed by agreeing to view the film in the White House. In Griffith's words, by viewing the film in the White House, Wilson "conferred" an "honor" upon The Birth of a Nation. The screening was in itself a tacit endorsement sufficient to protect the film from censors and to allow it to be shown around the country.” Benbow, “Birth of a Quotation.”

Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology, 24.

Marx, The German Ideology. Critique of Modern German Philosophy According to Its Representatives Feuerbach, B. Bauer and Stirner, and of German Socialism According to Its Various Prophets.

Hall, Notes on Deconstructing The Popular, 484.

Žižek, The Plague of Fantasies, 144-148.

Fisher, Capitalist Realism, 6-13.

This confused many people as really only Stanfield could be argued to be a supporting character, with Kaluuya clearly being the lead actor in portraying Fred Hampton. This was done so that Judas and the Black Messiah stood a better chance of winning an Oscar in an acting category, as the Best Actor Oscar was widely assumed as being guaranteed to be posthumously awarded to Chadwick Boseman. In an odd twist it ended up going to Anthony Hopkins, who wasn’t even at the ceremony, given said previous assumption. This also speaks to the production behind Judas and the Black Messiah as being crafted, from its inception, to appeal to broad sensibilities and clean up at the Oscars.